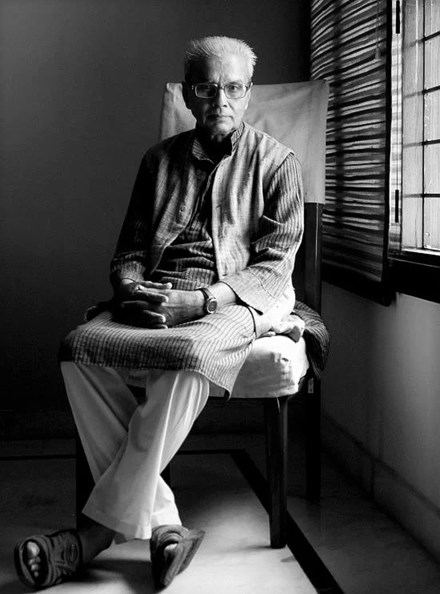

Kedarnath Singh

Kedarnath Singh, nasceu em 1934 em Chakia, uma pequena vila no norte da Índia. Trabalhou como professor de Hindi em várias cidades. Viveu muitos anos em Benares (Varanasi), cidade que o marcou profundamente.

É um poeta consagrado, autor de 7 obras de poesia, vários livros em prosa e traduções. Faz parte do movimento “escritores progressistas”. O seu estilo é simples e a sua linguagem clara. A sua obra revela uma consciência mítica e rural e evoca a presença silenciosa do misterioso e do mágico nos acontecimentos reais do dia a dia. Kedarnath Singh é também crítico literário e editor da revista Shabd (Palavra).

Kedarnath Sing morreu no dia 19 de março de 2018, em Nova Deli

Ver mais: biography and lectures/ wiki / poetryinternational /

Viens

Si tu trouves le temps

Et si tu ne trouves pas le temps

Viens quand meme

Viens

Comme dans les mains

Jaillit la force

Comme dans les artères

Coule le sang

Comme les flames douces

Dans l’âtre

Viens

Viens comme après la pluie

à l’acacia poussent

De tendres épines

Jours

Envolés

Promesses

Evanouies

Viens

Viens comme après le mardi

Arrive le mercredi

Viens

Tradução: Ingrid Therwath

(poema encontrado por uma amiga na revista "Lire")

Words don’t die of cold

they die from a lack of courage

Words often perish

because of humid weather

I once met

a word

that was like a bright red bird

in the swamp along the riverbank in my village

I brought it home

but as soon as we reached the wooden door-frame

it gave me

a strangely terrified look

and breathed its last

After that I started fearing words

If I ran into them I beat a hasty retreat

if I saw a hairy word dressed in brilliant colours

advancing towards me

I often simply shut my eyes

Slowly after a while

I started to enjoy this game

One day for no reason at all

I hit a beautiful word with a stone

while it hid

like a snake in a pile of chaff

I remember its lovely glittering eyes

down to this day

With the passage of time

my fear has decreased

When I encounter words today

we always end up asking after each other

Now I’ve come to know

many of their hiding-places

I’ve become familiar with

many of their varied colours

Now I know for instance

that the simplest words

are brown and beige

and the most destructive

are pale yellow and pink

Most often the words we save

for our saddest and heaviest moments

are the ones

that on the occasions meant for them

seem merely obscene

And what shall I do now

with the fact that I’ve found

perfectly useless words

that wear ugly colours

and lie discarded in the garbage

to be the most trustworthy

in my moments of danger

It happened just yesterday –

half a dozen healthy and attractive words

suddenly surrounded me

in a dark street

I lost my nerve –

For a while I stood before them

speechless

and drenched in sweat

Then I ran

I’d just lifted my foot in the air

when a tiny little word

bathed in blood

ran up to me out of nowhere panting

and said –

‘Come, I’ll take you home’

Tradução: Vinay Dharwadker

A TWO-MINUTE SILENCE

Brothers and sisters

this day is dying

a two-minute silence

for this dying day

for the bird flying away

for the still water

for the night-fall

a two-minute silence

for that which is

for that which is not

for that which could have been

a two-minute silence

for the discarded peel

for the crushed grass

for every plan

for every project

a two-minute silence

for this great century

for every great idea

of this great century

for its great words

and great intentions

a two-minute silence

brothers and sisters

for these great achievements

a two-minute silence.

A FOLKTALE

When the king died

his body was laid

in large coffin of gold.

A handsome body

no one who saw it

doubted that it was

the body of a king.

First the minister came

and stood with his head bowed

before the body

then the priest came

and mumbled something

under his breath for a long time

then the elephant came

and raised its trunk

in honour of the body

then the black and white horses came

but confused

by the grimness of the scene

they couldn’t decide

whether they should neigh.

Slowly – very slowly

came

the carpenter

the washer-man

the barber

the potter . . .

they stood around the magnificent coffin.

A strange sadness surrounded

the coffin.

Everyone was sad

the minister was sad

because the elephant was sad

the elephant was sad

because the horses were sad

the horses were sad

because the grass was sad

the grass was sad

because the carpenter was sad . . .

EVEN WITHOUT GOD

How strange it is

that at ten in the morning

the world is still going about its business

even without God.

The buses are crowded

and as usual

people are in a hurry.

His bag slung on his shoulder

the postman

is making his rounds as usual

even without God.

Banks somehow open on time

grass continues to grow

all calculations – however complicated –

somehow add up in the end

the one who must live

lives

the one who must die

dies

even without God.

How strange it is

that trains

late or on time

depart from and arrive at

some station or the other

that elections are held

planes continue to fly in the sky

even without God.

Even without God

horses continue to neigh

salt is still made in the sea

a sparrow

flies here and there

in a frenzy all day

and somehow finds her way

back to her nest

even without God.

Even without God

my sorrow is as profound as ever

and the hair of the woman

I had loved ten years ago

is as black as ever

and it is still as fascinating

to go out of this house

and then return home.

How strange it is

that water still flows

and the bridge still stands

in the middle of the stream

with its arms outstretched

even without God.

Tradução: Alok Bhalla